LIZZIE

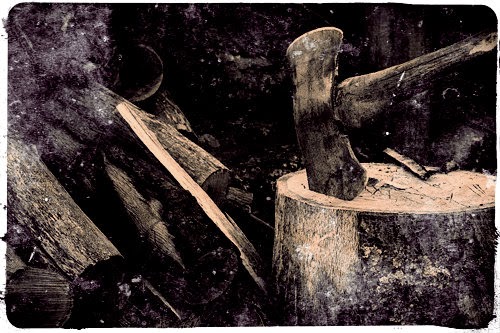

BORDEN TOOK AN AX?

But

Did She Really?

Lizzie Borden took an

axe

And gave her mother forty whacks.

And when she saw what she had done,

She gave her father forty-one.

The August afternoon

was unbearably hot, especially for Massachusetts. The temperature had climbed

to well over 100 degrees, even though it was not yet noon. The old man, still

in his heavy morning coat, was not feeling well and he reclined on a

mohair-covered sofa in the parlor, leaning back so that his boots were resting

on the floor and soiling the upholstery of the couch. In a short time, he

drifted off to sleep, never suspecting that he would not awaken.

He also did not

suspect that, above his head, his wife was bleeding on the floor of the

upstairs guestroom. She had been dead for nearly two hours and in moments, the

same hand that took her life would take the life of the old man’s as well.

And even if he knew

those things by way of some macabre premonition, he might never guess that his

murderer would never be brought to justice.

The

case of Lizzie Borden has fascinated those with an interest in American crime

for well over a century. There have been few cases that have attracted as much

attention as the hatchet murders of Andrew Borden and his wife, Abby. This is

partly because of the gruesomeness of the crime but also because of the

unexpected character of the accused. Lizzie Borden was not a slavering maniac

but a demure, respectable, spinster Sunday School teacher. Because of this, the

entire town was shocked when she was charged with the murder of her parents.

The fact that she was found to be not guilty of the murders, leaving the case

to be forever unresolved, only adds to the mystique and fans the flames of our

continuing obsession with the mystery.

From Left to Right: Andrew Jackson Borden /

Abby Durfree Gray Borden/ Emma Borden

Andrew

Jackson Borden was one of the leading citizens of Fall River, Massachusetts, a

prosperous mill town and seaport. The Borden family had strong roots to the

community and had been among the most influential citizens of the region for

decades. At the age of 70, Borden was certainly one of the richest men in the

city. He was a director on the board of several banks and a commercial landlord

with considerable holdings. He was a tall, thin and dour man and while he was

known for this thrift and admired for his business abilities, he was not

well-known for his humor, nor was he particularly likable.

Borden

lived with his second wife, Abby Durfee Gray and his daughters from his first

marriage, Emma and Lizzie, in a two-and-a-half story frame house. It was located

in an unfashionable part of town, but was close to his business interests. Both

daughters felt the house was beneath their station in life and begged their

father to move to a nicer place. Borden’s frugal nature never even allowed him

to consider this. In spite of this, and his conservative daily life, Borden was

said to be moderately generous with both of his daughters.

The

events that would lead to tragedy began on Thursday, August 4, 1892. The Borden

household was up early that morning as usual. Emma was not at home, having gone

to visit friends in the nearby town of Fairhaven, but the girls’ Uncle John had

arrived the day before for an unannounced visit. John Morse, the brother of

Andrew Borden’s first wife, was a regular guest in the Borden home. He traveled

from Dartmouth, Massachusetts several times each year to visit the family and

conduct business in town.

The

Borden House at 92 Second Street & the barn at the rear, where Lizzie

claimed to be during the murders

The

first person awake in the house that morning was Bridget Sullivan, the maid.

Bridget was a respectable Irish girl who Emma and Lizzie both rudely insisted

on calling "Maggie,” which was the name of a previous girl who had worked

for them. At the time of the murders, Bridget was 26 years old and had been in

the Borden household since 1889. There is nothing to say that she was anything

but an exemplary young woman, who had come to America from Ireland in 1886. She

did not stay in the house during the night following the murders, but did come

back on Friday night to her third-floor room. On Saturday, she left the house,

never to return.

Bridget

came downstairs from her attic room around 6:00 a.m. to build a fire in the

kitchen and begin cooking breakfast. An hour later, John Morse and Mr. and Mrs.

Borden came down to eat and they lingered in conversation around the table for

nearly an hour. Lizzie slept late and did not join them for the meal.

The Borden's maid,

Bridget Sullivan

At

a little before 8:00 a.m., Morse left the house to go and visit a niece and

nephew and Borden locked the screen door after him. It was a peculiar custom in

the house to always keep doors locked. Even the doors between certain rooms

upstairs were usually locked. A few minutes after Morse left, Lizzie came

downstairs but said that she wasn’t hungry. She had coffee and a cookie but

nothing else. It’s possible that she had a touch of the stomach disorder that

was going around the household. Bridget later stated that she felt the need to

go outside and throw up some time after breakfast. Two days before, Mr. and

Mrs. Borden had been ill during the night and had both vomited several times.

It has been assumed that this may have been food poisoning as no one else in

the family was affected. It may have been the onset of the flu -- or something

far more sinister.

At

a quarter past nine, Andrew Borden left the house and went downtown. Abby

Borden went upstairs to make the bed in the guestroom that Morse was staying

in. She asked Bridget to wash the windows. At 9:30, she came downstairs for a

few moments and then went back up again, commenting that she needed fresh

pillowcases. Bridget went about her daily chores and started on the window

washing, retrieving pails and water from the barn. She also paused for a few

minutes to chat over the fence with the hired girl next door. She finished the

outside of the windows at about 10:30 a.m. and then started inside.

Fifteen

minutes later, Mr. Borden returned home. Bridget let him in and Lizzie came

downstairs. She told her father that "Mrs. Borden has gone out - she had a

note from someone who was sick." Lizzie and Emma always called their

step-mother "Mrs. Borden" and recently, the relationship between them,

especially with Lizzie, was strained.

Borden

took the key to his bedroom off a shelf and went up the back stairs. The room

could only be reached by these stairs, as there was no hallway, and the front

stairs only gave access to Lizzie’s room (from which Emma’s could be reached)

and the guest room. There were connecting doors between the elder Borden’s

rooms and Lizzie’s room, but they were usually kept locked.

Borden

stayed upstairs for only a few minutes before coming back down and settling

onto the sofa in the sitting room. Lizzie began to heat up an iron to press

some handkerchiefs. "Are you going out this afternoon, Maggie?" she

asked Bridget. "There is a cheap sale of dress goods at Sargent’s this

afternoon, at eight cents a yard."

Bridget

replied that she was not. The heat of the morning, combined with the window

washing and her touch of stomach ailment, had left her feeling poorly and she

went up the back stairs to her attic room for a nap. This was a few minutes

before 11:00 a.m. She was awakened a few minutes later by a cry from

downstairs.

"Maggie,

Come down!" Lizzie shouted from the bottom of the back stairs and

Bridget’s eyes fluttered open. She had drifted off into a restless sleep but

the urgency of Lizzie’s cries startled her awake. Bridget replied in a

flustered voice, asking what was wrong.

"Come

down quick!" Lizzie wailed, "Father's dead! Somebody's come in and

killed him!"

As

Bridget hurried from the staircase, she found Lizzie standing at the back door.

Her face was pale and taut. She stopped the young maid from going into the

sitting room and ordered her to go and fetch a doctor.

Dr.

Bowen, a family friend, lived across the street from the Bordens’ and Bridget

ran directly to the house. The doctor was out, but Bridget told Mrs. Bowen that

Mr. Borden had been killed. She ran directly back to the house. Mrs. Bowen

asked Lizzie where she had been when the murder occurred and she said she was out

in the yard, heard a groan and came inside. This was the first version she

would give of her movements that morning – various others would follow.

Lizzie

sent Bridget to summon a friend of the Borden sisters, Alice Russell, who lived

a few blocks away and by now, neighbors were starting to gather on the lawn and

someone had called for the police. Mrs. Adelaide Churchill, the next door

neighbor, came over to Lizzie, who was at the back entrance to the house and

asked if anything was wrong. Lizzie responded by saying, "Oh, Mrs.

Churchill, someone has killed Father!"

She

explained that her father was in the sitting room and asked where she was when

he was killed, she stated that she had been in the barn, getting a piece of

iron. She didn’t know where Abby Borden was, stating that she had gone out to

visit a sick friend. But she added, “But I don’t know but that she is killed

too, for I thought I heard her come in... Father must have an enemy, for we

have all been sick, and we think the milk has been poisoned."

Andrew Borden's bloody corpse was

discovered on his favorite downstairs sofa.

Abby Borden's body was

found upstairs. She was struck from behind, likely while on her knees making

the bed.

By

this time, Dr. Bowen had returned, along with Bridget, who had hurried back

from informing Miss Russell of the day’s dire events. Dr. Bowen examined the

body and asked for a sheet to cover it. Borden had been attacked with a sharp

object, probably an ax, and so much damage had been done to his head and face

that Bowen, a close friend, couldn’t positively identify him at first. Borden’s

head was turned slightly to the right and eleven blows had gashed his face. One

eye had been cut in half and his nose had been severed. The majority of the

blows had been struck within the area that extended from the eyes and nose to

the ears. Blood was still seeping from the wounds and had been splashed onto

the wall above the sofa, the floor and on a picture hanging on the wall. It

looked as though Borden had been attacked from above and behind as he

slept.

Several

minutes passed before anyone thought of going upstairs to see if Abby Borden

had come home. Lizzie, who previously was sure that Abby was out of the house,

now stated that she thought she heard her come inside. She ordered Bridget to

go upstairs and check, but the maid refused to go alone. Mrs. Churchill offered

to go with her. They went up the staircase together but Mrs. Churchill was the

first to see Abby lying on the floor of the guestroom. She had fallen in a pool

of blood and Mrs. Churchill later said that she had been so savagely attacked

that she only "looked like the form of a person."

Dr.

Bowen found that Mrs. Borden had been struck more than a dozen times, from the

back. The autopsy later revealed that there had been nineteen blows to her

head, probably from the same hatchet that had killed Mr. Borden. The blood on

Mrs. Borden's body was dark and congealed, leading him to believe that she had

been killed before her husband.

Dr.

Bowen was heavily involved in the activities of the Borden house on the day of

the murder. He was the first to examine the bodies, sent a telegram to Emma to

summon her home, assisted Dr. Dolan with the autopsies and even prescribed a

calming tranquilizer for Lizzie. He was a constant presence in the house and

his involvement with them, especially on August 4, has led to him being

considered a major figure in some of the conspiracies developed around the

murders.

A

call reached the Fall River police station at 11:15 a.m., but as things would

happen, that day marked the annual picnic of the Fall River Police Department

and most of them were off enjoying an outing at Rocky Point. The only officer

dispatched to the house was Officer George W. Allen. He ran to the house, saw

that Andrew Borden was dead and ran back to the station house to inform the

city marshal of the events. He left no one in charge of the crime scene. While

he was gone, neighbors overran the house, comforting Lizzie and peering in at

the gruesome state of Andrew Borden’s body. The constant traffic trampled and

destroyed any clues that might have been left behind.

During

the half hour or so that no authorities were on the scene, a county medical

examiner named Dolan passed by the house by chance. He looked in and was

pressed into service by Dr. Bowen. Dolan examined the bodies and after hearing

that the family had been sick and that the milk was suspected, he took samples

of it. Later that afternoon, he had the bodies photographed and then removed

the stomachs and sent them, along with the milk, to the Harvard Medical School

for analysis. No poison was ever found.

The

murder investigation that followed was chaotic. The police were reluctant to

suspect Lizzie of the murder as it was against the perceived social

understanding of the era that a woman such as she was could have possibly

committed such a heinous crime. Other solutions were advanced but were

discarded as even more improbable.

A

profusion of clues were discovered over the next few days, all of which led

nowhere. A boy reported seeing a man jump over the back fence of the Borden

property and while a man was found matching the boy’s description, he had an

unbreakable alibi. A bloody hatchet was found on the Sylvia Farm in South

Somerset but it proved to be covered in chicken blood. While Bridget was

considered a suspect for a short time, the investigation finally began to

center on Lizzie. A circumstantial case began to be developed against her with

no incriminating physical evidence, like bloody clothes, a real motive for the

killings, or even a convincing demonstration of how and when she committed the

murders.

Over

the course of several weeks, though, investigators managed to compile a

sequence of events that certainly cast suspicion on the spinster Sunday School

teacher. The timeline ran from August 3, the day before the murders to August

7, the day that Alice Russell saw her friend burning a dress that may (or many

not) have had blood on it. The timeline is as follows:

August 3

The

timeline began in the early morning hours when Abby Borden sent for Dr. Bowen

and told him that she and her husband had been sick and vomiting during the night.

He did not believe the illness was serious and there would be no evidence of

poisoning found in the Borden autopsies.

Another

incident took place when Lizzie tried to buy ten cents worth of prussic acid

from Eli Bence, a clerk at Smith’s Drug Store. She explained to him that she

wanted the poison to "kill moths in a sealskin cape" but he refused

to sell it to her without a prescription. A customer and another clerk also

identified Lizzie as being in the store that morning, but she denied it. She

testified at the inquest that she had not attempted to purchase the poison and

had not been at the drugstore that day.

The

third incident was the arrival of John Morse in the early afternoon. He came

without luggage but intended to stay the night. Both he and Lizzie testified

that they did not see each other until after the murders the next day, although

Lizzie knew that he was there.

Finally,

that evening Lizzie visited her friend, Miss Alice Russell. According to Miss

Russell, Lizzie was agitated, worried over some threat to her father, and

concerned that something was about to happen. Borden had a number of enemies

made during business dealings and she claimed to be frightened that something

might happen to the family.

August 4

Abby

was killed, according to the autopsy, at around 9:30 a.m. The killer, if it was

anyone but Lizzie or Bridget, would have had to have concealed himself (or

herself) in the house for well over an hour, waiting for Andrew Borden’s

return. Abby could have been discovered at any moment.

Abby’s

time of death also posed another problem for investigators. According to

Lizzie, she had gone out but she obviously hadn’t. The note that Lizzie said

that Abby had received, asking her to visit a sick friend, was never found.

Lizzie later said that she might have inadvertently thrown it away.

When

Andrew Borden returned to the house, Bridget had to let him in as the screen

door was fastened on the inside with three locks. This would have made it

extremely difficult for the killer to get inside. Only a small window of

opportunity would have existed while Bridget was fetching a pail and water from

the barn. In addition, Bridget later testified that while she was unlocking the

door for Mr. Borden, she heard Lizzie laugh from upstairs. However, Lizzie

swore that she had been in the kitchen when her father came home.

Borden

also had to retrieve the key to his bedroom from the shelf in the kitchen to

get into his room. This was done as a precaution because of a burglary the year

before. In June 1891, a police captain inspected the house after Andrew Borden

reported a crime. Borden’s desk had been rummaged through and $100 and a watch

and chain had been taken. There was no clue as to how anyone could have gotten

into the house, although Lizzie offered the fact that the cellar door had been

open. The neighborhood was canvassed but no one reported seeing a stranger in

the vicinity. According to the police captain, Borden said several times to

him, "I’m afraid the police will not be able to find the real thief."

It is unknown what he may have meant by this but various conspiracy theorists

have their own ideas.

On

the afternoon of the murder, four hatchets were discovered in the basement of

the house, including one with dried blood and hair on it (later determined to

be from a cow). Another of the hatchets was rusted and the others were covered

with dust. One of these was without a handle and was covered in ashes. The

broken handle appeared to be recent, so it was taken into evidence.

A

Sergeant Harrington and another officer asked Lizzie where she had been that

morning and she said that she had been in the barn loft looking for iron for

fishing sinkers. The two men examined the barn and found the loft floor to be

thick with dust, with no evidence that anyone had been up there.

Deputy

Marshal John Fleet questioned Lizzie and asked her who might have committed the

murders. Other than an unknown man with whom her father had gotten into an

argument with a few weeks before, she could think of no one. When asked

directly if Uncle John Morse or Bridget could have killed her father and mother,

she said that they couldn't have. Morse had left the house before 9:00 a.m.,

and Bridget had been sleeping when Andrew had been killed. She pointedly

reminded Fleet that Abby was not her mother, but her stepmother.

August 5

The

investigation continued on the day after the murders. By now, the story had

appeared in the newspapers and the entire town was in an uproar. Sergeant

Harrington found Eli Bence at Smith’s Drug Store and interviewed him about the

attempt to buy poison. Emma engaged Mr. Andrew Jennings as their family attorney.

The police continued to investigate, but nothing of significance was

found.

August 6

The

funerals of the Bordens took place on Saturday. The service was conducted by

the Reverends Buck and Judd, from the two Congregational Churches. The bodies

were not buried at that time. The police arrived and removed the bodies for

another autopsy. The heads of the Bordens were removed from the body, the skin

removed and plaster casts were made of the skulls. For some reason, Mr.

Borden’s head was not returned to his coffin.

August 7

On

Sunday morning, Alice Russell observed Lizzie burning a dress in the kitchen

stove. She told Lizzie, "If I were you, I wouldn't let anybody see me do

that." Lizzie said it was a dress stained with paint and was of no

use.

It

was this testimony from Miss Russell at the inquest that prompted Judge

Blaisdell of the Second District Court to charge Lizzie with the murders. The

inquest itself was kept secret but at its conclusion, Lizzie was charged and taken

into custody. The only testimony that Lizzie ever gave during all of the legal

proceedings was at the inquest and we will never know what she said for the

records were sealed. She was arraigned the following day and entered a not

guilty plea. She was then taken to the Taunton Jail, which had facilities for

female prisoners.

After

that, Judge Blaisdell held a preliminary hearing. Lizzie did not testify but

the record of her testimony at the inquest was entered into evidence by her

attorney, Andrew Jennings. The judge declared her probable guilt and bound

Lizzie over for the grand jury, who heard the case during the last week of its

session.

The

Commonwealth, represented by prosecutor Hosea Knowlton, had the disagreeable

task of building the case against Lizzie. When he finished his presentation to

the Grand Jury, he surprisingly invited defense attorney Jennings to present a

case for the defense. This was something that was simply not done in

Massachusetts. In effect, a trial was being conducted before the Grand Jury.

Many saw this is as a chance that the charge against Lizzie might be dismissed.

Then, on December 1, Alice Russell again testified about the burning of the

dress. The next day, Lizzie was charged with three counts of murder. Strangely,

she had been charged with the murder of her father, her step-mother and then

the murders of both of them. The trial was scheduled to begin on June 5,

1893.

The

trial itself lasted fourteen days and news of it filled the front pages of every

major newspaper in the country. Between 30 and 40 reporters from the Boston and

New York papers and the wire services were in the courtroom every day. The

trial began on June 5 and after a day to select the jury, which consisted of

twelve middle-aged farmers and tradesmen, the prosecution spent the next seven

days putting on its case.

Hosea

Knowlton was the reluctant prosecutor in the case. He had been forced into the

role by Arthur Pillsbury, Attorney General of Massachusetts, who should have

been the principal attorney for the prosecution. However, as Lizzie's trial

date approached, Pillsbury felt the pressure building from Lizzie's supporters,

particularly women's groups and religious organizations. Worried about the next

election, he directed Knowlton, who was the District Attorney in Fall River, to

lead the prosecution in his place. He also assigned William Moody, District

Attorney of Essex County, to assist him.

Moody

made the opening statements for the prosecution. He presented three arguments. First,

that Lizzie was predisposed to murder her father and stepmother because of

their animosity toward one another. Second, that she planned the murder and

carried it out and third, that her behavior, and her contradictory testimony,

after the fact was not that of an innocent person. Moody did an excellent job

and many have regarded him as the most competent attorney involved in the case.

At one point, he threw a dress onto the prosecution table that he planned to

admit as evidence. As he did so, the tissue paper that was covering the skull

of Andrew Borden lifted and then fluttered away. Dramatically, Lizzie slid to

the floor in a dead faint.

Crucial

to the prosecution in the case was evidence that supplied a motive for Lizzie

to commit the murders. This was done by using a number of witnesses who

testified to Lizzie’s dislike of her step-mother and her complaints about her

father’s spendthrift ways. The prosecution also tried to establish that Borden

was writing a new will that would leave Emma and Lizzie with a pittance and

Abby with a huge portion of his estate. One of the witnesses called to

establish this was John Morse, who first said that Andrew discussed a new will

with him and then later said that he never told him anything about it.

The

prosecution then turned to Lizzie’s predisposition towards murder and her

strange behavior before and after the events. They again called Alice Russell

to testify about the burning of the dress. The destruction of it seemed a

possible answer as to why Lizzie was not covered with blood after killing her

parents. It was highly probable that she would have been spattered with it if

she did commit the murders. In later years, some have theorized that perhaps

she wore a smock over her dress during the murders or that perhaps she was

naked when she did it. However, the smock would have been bloody and also would

have had to be disposed of. As far as Lizzie being naked, this seems doubtful

too. Ignore the fact that in the Victorian society of Fall River, a young woman

would have never appeared nude in front of her father (even to kill him) and

focus on the fact that Lizzie never had time to bathe after killing Abby or in

the few minutes between the killing of Andrew and her calling for Bridget.

To

the prosecution, though, the burning of the dress suggested that Lizzie had

changed clothing after the murders. But why would she have kept the dress for

three days before burning it and what would she have worn for the hours between

the two deaths? Someone would have surely noticed a dress covered with

blood.

On

Saturday, June 10, the prosecution attempted to enter Lizzie's testimony from

the inquest into the record. The defense objected, since it was testimony from

one who had not been formally charged. The jury was withdrawn so that the

lawyers could argue it out and on Monday, when court resumed, the three-judge

panel excluded Lizzie’s contradictory inquest testimony.

On

Wednesday, June 14, the prosecution called Eli Bence, the drug store clerk, to

the stand. The defense objected to his testimony as irrelevant and prejudicial.

The judges sustained the objection and Lizzie’s attempt to buy poison was

thrown out of the record.

The

prosecution called several medical witnesses, including Dr. Dolan. One of them

even produced the skull of Andrew Borden to show how the blows had been struck.

Unfortunately for the prosecution, these witnesses had an adverse effect on the

case as the defense used their testimonies to strike points in Lizzie’s favor.

They were forced to state that whoever had committed the murders would have

been covered with blood. There was no witness to say that blood was ever found

on Lizzie.

Lizzie

Borden’s defense counsel used only two days to present its case. For the most

part, the defense offered witnesses who could either corroborate Lizzie’s

story, or who could provide alternate possibilities as to who the killer might

be. The testimony of the various witnesses was meant to do little but provide

"reasonable doubt" about Lizzie’s guilt.

For

instance, an ice cream peddler testified to seeing a woman (presumably Lizzie)

coming out the barn. This bolstered her story that she had actually been there.

A passer-by claimed to see a "wild-eyed man" around the time of the

murders. Mr. Joseph Lemay claimed that he was walking in the deep woods, some

miles from the city, about twelve days after the murders when he heard someone

crying "Poor Mrs. Borden! Poor Mrs. Borden! Poor Mrs. Borden!" He

said that he looked over a wall and saw a man sitting on the ground. The man,

who had bloodstains on his shirt, picked up a hatchet, shook it at him and then

disappeared into the woods. The defense also called witnesses who claimed to

see a mysterious young man in the vicinity of the Borden house who was never

properly explained. They also called Emma Borden to dispute the suggestion that

Lizzie had any motive to want to kill their parents.

On

Monday, June 19, Robinson delivered his closing arguments and Knowlton began

his closing arguments for the prosecution. He completed them on the following

day. The judges then asked Lizzie if she had anything to say for herself and

she spoke for the only time during the trial. She said: “I am innocent. I leave

it to my counsel to speak for me.” Instructions were then given to the jury and

they left to deliberate over the verdict.

A

little over an hour later, the jury returned with its verdict. Lizzie Borden

was found "not guilty" on all three charges. Public opinion was, by

this time, of the feeling that the police and the courts had persecuted Lizzie

long enough.

Five

weeks after the trial, Lizzie (who henceforth called herself

"Lizbeth") and Emma purchased and moved into a thirteen-room, stone

house at 306 French Street in Fall River. It was located on "The

Hill", the most fashionable area of the city. Lizzie named the house

"Maplecroft" and had the name carved into the top step leading up to

the front door.

Lizzie's

(or Lizbeth's) home in Fall River, Maplecroft.

In

1904, Lizzie met a young actress, Nance O'Neil, and for the next two years,

Lizzie and Nance were inseparable. About this time, Emma separated from her

sister and moved to Fairhaven. She and Lizzie stopped speaking to one another.

Rumors said that sensational revelations about the murders would follow the

split, but the revelations never came. Emma stayed with the family of Reverend

Buck, and, sometime around 1915, she moved to Newmarket, New Hampshire.

Lizzie

died on June 1, 1927, at age 67, after a long illness from complications

following gall bladder surgery. Emma died nine days later, as a result of a

fall down the back stairs of her house in Newmarket. They were buried together

in the family plot, along with a sister who had died in early childhood, their

mother, their stepmother, and their headless father. Both Lizzie and Emma left

their estates to charitable causes and Lizzie designated $500 for the perpetual

care of her father’s grave.

Bridget

Sullivan never worked for any of the Bordens again. After the terrible events

of the murder and the trial, she left town. She lived in modest circumstances

in Butte, Montana until her death in 1948. Those who suggested that she had

been "paid off" to keep quiet about the murders could find no

evidence of this in what she left behind.

Many

years have passed since the murders in Fall River and they remain unsolved. No

single theory has ever been regarded as the correct one and every writer on the

case seems to have a favorite culprit. Many books and articles have been written

about the case, but each writer puts their own spin on the story. During the

early days of the investigation, and well into the days of the trial, a number

of accusations were made. At times, the killer was said to be John Morse,

Bridget Sullivan, Emma Borden, Dr. Bowen and even one of Lizzie’s Sunday School

students. Since that time, there have been other suggested killers. Some of the

theories are credible and some are not.

One

of the theories remains that Lizzie Borden actually committed the murders of

her parents and managed to get away with it. This theory was especially popular

in books written prior to 1940, but many believe it today. Most of the writers

who stand by this solution see the court rulings and poorly executed

prosecution case as the reason that Lizzie was never found guilty. They simply

refuse to see how an outsider could have committed the crimes. But there is that

problem of all of the blood. If Lizzie did kill her step-mother, where was the

blood that would have been on her dress when she called Bridget a short time

later? If she did change clothing (twice in the same morning), wouldn’t Bridget

have noticed this? It has been suggested that Lizzie may have gone to the barn

between the murders as she claimed to and washed the blood off (there was

running water there), but if she did, how did she wash off the blood after her

father’s murder?

Some

writers believe that Lizzie and Bridget planned the murders together and that

Bridget (when she went to Alice Russell’s house) spirited away the bloody

hatchet and dress so that they were never found. This theory is also used to

explain the testimony that each woman gave about the day of the murder, never

implicating the other. It seems hard to believe that Abby Borden’s fall to the

upstairs floor would not have been heard from below, especially since Abby

weighed nearly 200 pounds. However, there is no proof of this either and it

still places one or both of the women in the role of a depraved killer.

While

it seems hard to believe that Lizzie did commit the murders, it doesn’t mean

that she was not guilty in other ways. In other words, while she may not have

actually handled the hatchet, she may have known who did.

One

person who has been accused in this capacity was Emma Borden. It has been noted

with some suspicion how she may have arranged an alibi for herself, claiming to

be some 15 miles away in Fairhaven, but actually returned to Fall River, hid

upstairs in the Borden house, committed the murders and then returned to

Fairhaven, where she received the telegram from Dr. Bowen. Once Lizzie is

accused, the two sisters worked together to protect each other. Later, the

women had a falling out over their father’s estate. But we will never know.

Neither woman ever spoke of the murder again.

Another

theory accuses William Borden, the illegitimate son of Andrew Borden, who committed

suicide a few years after the trial. According to this theory, Lizzie, Emma,

John Morse, Dr. Bowen and Andrew Jennings all conspired to keep his involvement

a secret because of his illegitimate status and a claim that he might make

against the estate if his relationship with the Borden’s was found out.

Allegedly, William was making demands of his father, who was in the process of

writing a new will. Borden rejected the boy and William became enraged. He

first killed Mrs. Borden and then after hiding in the house -- with Lizzie’s

knowledge -- killed his father. The conspirators then either paid William off

or threatened him, or both, and decided that Lizzie would allow herself to be

suspected and tried for the murders, knowing that she could always identify the

real killer, should that be necessary. There’s a lot of speculation with this

theory, but it’s as possible as so many others.

So

who did kill Andrew and Abby Borden? It’s unlikely that we will ever know. It’s

also unlikely that we will ever discover just what Lizzie, and her defense

counsel, really knew about the events in 1892. The papers from Lizzie’s defense

are still locked up and have never been released. The files remain sealed away

in the offices of the Springfield, Massachusetts law firm that descended from

the firm that defended Lizzie during the trial. There are no plans to ever

release them.

The

history of the Lizzie Borden case lingers in our collection imaginations, much

like the spirits that are still believed to linger at the former Borden house

in Fall River, Massachusetts, which now serves as a bed and breakfast. More

than one overnight guest has claimed an encounter with one of the ghosts that

remain from the brutal murders. The truth behind such stories remains as

elusive as the killer of the Bordens – but the speculation will certainly never

end.

Author Troy Taylor

has a book on the Lizzie Borden case planned for later in 2014. Keep an eye on

the Whitechapel Press website for upcoming information.